We live in the Information Age where the world has never been more connected. Decades of technological developments like Global Transportation and Digitalisation have massively increased connectivity between people, places, products, and processes.

The world is more connected than ever before

We live in the Information Age where the world has never been more connected. Decades of technological developments like Global Transportation and Digitalisation have massively increased connectivity between people, places, products, and processes. Whilst there have been significant benefits with this new connectivity, it has introduced trillions of new cause and effect relationships that never previously existed. As our societies have become more connected, the world of work has become more Volatile, Uncertain, Complex and Ambiguous than at any stage in human history.

The effects of rapid change are found in all professions

No profession or sector is immune. It's simultaneously a cliché and a paradox but change is one of the few constants in our world and the pace of change is accelerating. How can we deliver successful projects and programmes more often in this context?

The most prevalent project management methods were built in a different time

They implicitly place too much value on certainty; valuing determinism above all else. We only need to consider elements such as baselines, risk management and Earned Value Analysis to illustrate the point. This doesn't mean that they are all bad and should be avoided; it’s just that we need to adapt how we think about them and modify our approach accordingly.

Our brains are programmed to look for threats & crave certainty

We often don't help ourselves and we don't always know it. Our brains have evolved to look for threats in the environment and eliminate them. We evaluate situations based on what we have experienced before and fit the best pattern to them that we can. To make this energy efficient it happens sub-consciously. The more experience we have the more likely it is that we believe that we know what to do. Yet every situation, every project and every programme is unique and reassuringly so, since there would be no value in doing it if it wasn’t the case. The question that nobody knows the answer to at the start is how unique.

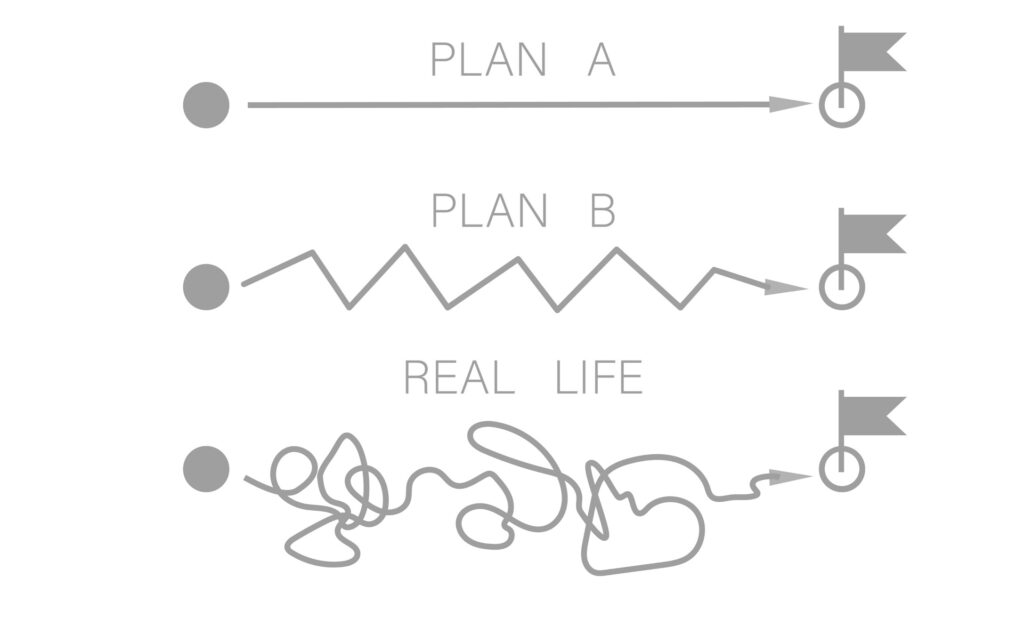

Where plans meet reality

Traditional Programme Management methods tend to result in plans that resemble Plan B. We tend to evaluate performance subconsciously with respect to Plan A. We encounter Real Life……We need a method of providing structure and a sense of direction whilst maintaining flexibility to respond and adapt to real life.

Knowledge threshold

We only know so much and we can only see so far. Once we acknowledge this we come to consider projects and programmes as voyages of discovery or vehicles for learning. We need a new collective thinking way to deliver success.

Scientific thinking

The thinking way has a name – Scientific Thinking. The process of “deliberately engaging with reality with the intent of learning”. Notice the words in the definition:

“deliberately” (planned with a purpose)

“engaging” (interacting with)

“reality” (something that actually happens)

with the “intent” (an objective)

of “learning” (discovering things that we didn’t already know).

In order to learn something specific and useful we must compare two things:

- What we expect to happen if we take action – in science this is often called an hypothesis

- And we need to experience what actually happened as a result of taking that action

When those two things are the same, we confirm our original hypothesis and we make progress in line with expectations. When those two things are different, we learn something new. In projects and programmes this new learning might help us to retire risk by removing assumptions. There are many studies that show that the most significant determinant of project performance is the speed and quality of decision making. We know that small experiments that accelerate our learning help us make faster and better decisions based on facts rather than assumptions. In Agile Project Management we would call this approach “Inspect & Adapt" or “Reflect & Adjust”.

Constructing projects as small experiments

We can improve the quality, cost and delivery of our projects and programmes if we construct our plans as multiple small, frequent experiments that integrate what we already know with activities to find out what we don't. To do this we must recognise our current state and the goal of the project or programme. We break the plan down into smaller chunks and establish short term targets for each. We plan activity with the hypothesis that taking a specific action or actions will lead us to meet the short term target condition. We test that hypothesis through action and adapt our knowledge and future actions accordingly (this cycle is often called the Deming Cycle).

Transparency from tools

There are tools available today that embrace this thinking. We can integrate milestones (what we know we need to achieve), what we know we need to do to achieve them with what we don't yet know we have to do to achieve them. There are many benefits to using these tools and the 3 key strengths from our perspective are:

- the flexibility to be configured to represent any situation that a team might face.

- the transparency that is provided to help everyone understand where we are, where we are going and the learning that is taking place.

- the transparency that results in the ability to collaborate effectively on a frequent basis even when teams are geographically dispersed.

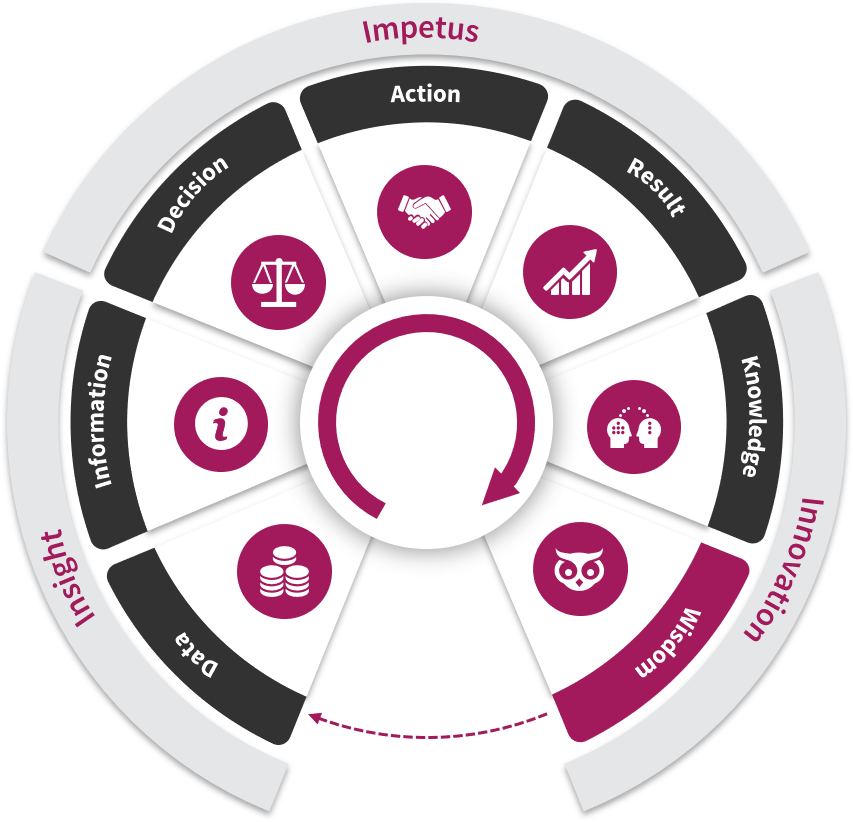

A helpful Learning Kata

We have distilled much of the thinking way that we described into a high level model for anyone faced with delivering projects in a VUCA world and a supporting Learning Kata. There are 3 main parts:

- Innovation: If we want to deliver new products, services or want to develop new ways of working we must learn or do different things.

- To do different things we must create Impetus or momentum to learn to enable us to deliver.

- To gain Impetus to deliver Innovation we must have the motivation to act. There must be a positive tension for action. This comes from Insights – new data and information that challenges our view of the way that the world works.

A famous model in this regard is the Senn-Delaney Results Cone, which neatly summarised the cycle as: Results are driven by Behaviours, which are driven by our Thinking, which is driven by the Insights that we gain.

To change our thinking patterns we need to experience repetitious cycles. A “Kata” refers to a form, routine, or pattern of behaviour that can be practiced to develop a skill to the point where it becomes second nature. Our Learning Kata builds on the cycle described above as follows.

We gain insight by obtaining data and turning it into information.

We generate impetus by using that information to decide what action to take. Once we take that action and get a result, we compare it with what we expected to happen.

This generates new knowledge and with multiple cycles creates wisdom. With new found knowledge and wisdom we can deliver innovation.

Delivering projects in a VUCA world

If our projects and programmes are built on this cycle with collaboration, transparency and adaptability at the heart they will deliver outstanding results. We can prosper in a VUCA world if we place greatest value on and deliberately plan to learn all of the things that we don't know that we think we should.